The attached range was originally constructed with five student rooms meant to house two students each, and the detached range was comprised of seven of these same types of student rooms. While there is no exact end date of the state student program documented, it likely ended during the Civil War when University attendance plummeted to only about fifty students. We do know that students were no longer occupying the dorms in the Monroe Hill range buildings at this time, as it is documented that in 1862 Confederate Capt. James McD. Carrington’s Virginia Light Artillery Unit sheltered in “the dormitories on Monroe Hill.” After the Civil War and the conclusion of the State Scholars program, we know that students continued to live in the Monroe Hill range buildings until some point in the twentieth century. The students left a variety of grafitti on both the interior and exterior of the dormitory buildings. Students carved things such as their names, years, and other symbols into the matels and doors inside the buildings and there is a great deal of writing on the penciling between bricks on the building's exteriors, and due to the covered walkway much of it has survived.

A memoir written by James Southall, a student living in the detached range on Monroe Hill in 1888 and 1889, gave us some fascinating insight into the layout and use of the buildings at that time. He explained that there was a fireplace in the center of one wall, and between the fireplace and the door was a closet with a wash basin that was partitioned off from the room with a curtain. On one side of the closet there were small shelves and on the other there were several hooks for hanging personal items. This room arrangement is consistent with the way that student dormitories were configured in the range buildings at the Academical Village. Southall also writes that in his room there was also a bookshelf secured to the wall in the corner on the other side of the door. This particular furnishing may have been provided by the University and common among the other rooms in the Monroe Hill ranges, or it may have been left behind by a previous student. He also wrote that since there was not space in the room for his dedicated bath tub, it was kept hanging on a nail secured in the mortar outside of his room.

Using a combination of Southall's memoir, Board of Visitors archives, Sanborn maps, and physical evidence, we were able to piece together a better idea of how the Monroe Hill range rooms were used in the second half of the nineteenth century. He goes into great detail listing the full names of every student that was living on Monroe Hill at the time that he stayed there. It seems that the rooms could be rented by either one student or two, with most being occupied by a single renter and a few of the rooms housing two students splitting the cost of rent, which was thirty dollars. Southall explains that Professor William M. Thornton, who was the Chairman of the Faculty during his time as a student at UVA, lived in the main house on Monroe Hill that was joined to the range by the two communicating rooms that he used for a library and study.

We believe that Southall’s description of Dr. Thornton’s residence and his occupation of the adjacent rooms explains the questions that we had surrounding the physical evidence we found of a door in the shed addition of the attached range. The small shed addition that sits behind the detached range butting up against the main house is currently incorporated into the range room that now serves as a student lounge. We were unsure as to when it was built or what it's originial purpose was. Interestingly, durring our fiedlwork we discovdered that evidence in the broickwork suggested that the current window was once a door. This didn't make sense with the narrative of the ranges as student housing and so we looked to the archival evidence to learn more.

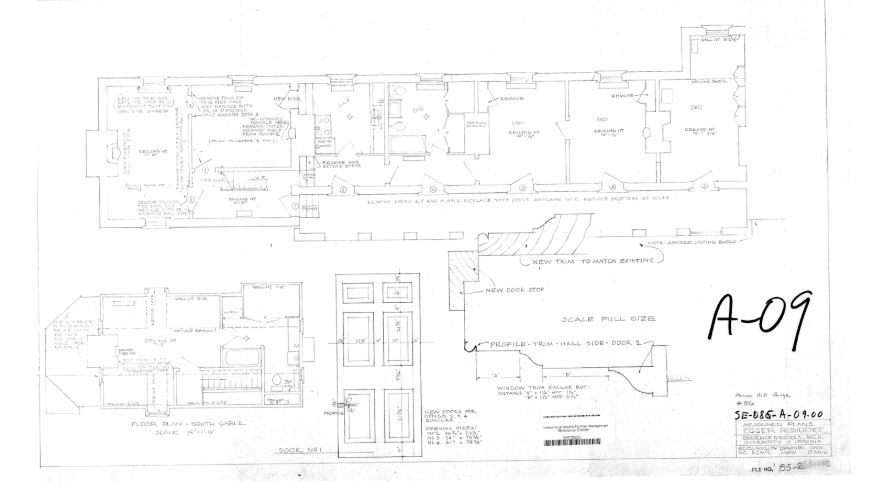

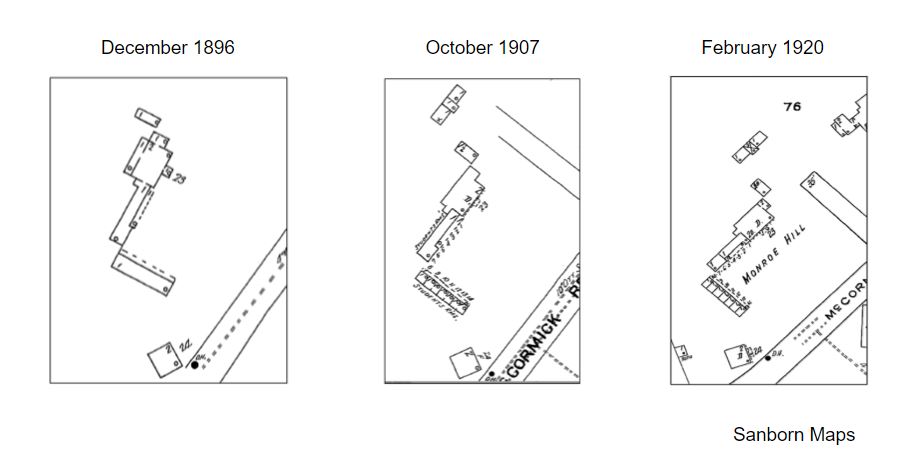

If Dr. Thornton was using this space for his own personal use, it would have made sense for it to be built with a door so that it was easily accessible to him from the rear. We found that the Board of Visitors notes indicate that there was a faculty member living in the main house on Monroe Hill at least as early as 1866, the year following the end of the Civil War, so it is possible that the range rooms nearest to the main house were repurposed for faculty use as early as this. The use of the small shed addition and its corresponding range room also explains why the addition was depicted in the Sanborn maps as being connected with the main house. Since the Sanborn maps for Monroe Hill were updated until 1950, this would indicate that the shed addition was changed to adjoin the range building at some point between this date and 1961, when the plans for the Egger Residence apartment depict the shed addition being connected only to the range building.

In his memoir, Southall then goes on the list the names of the students living in each room, beginning with those closest to the main house and working his way around the corner of the building complex to the south end of the detached range building. Interestingly, he does not mention anyone living in the office building, but he does indicate the students living in the “the two rooms in the angle of the L” in the range attached to Dr. Thornton’s house. We found the omission of an explanation of who was living in the office building to be significant, as every other room on Monroe Hill had been accounted for in his description. Additional archival records do not indicate any distinction being made of the law office until 1917, when it is mentioned for the first time in the Board of Visitors notes as being occupied by a professor at the University, in addition to the “adjacent rooms” being occupied by a second professor Prior to 1917, there was only ever mention of the main Monroe House being occupied by faculty and the two ranges which were occupied by students.

When taken together, the physical evidence of the mantelpieces and graffiti, the archival evidence of the Sanborn maps and the Board of Visitor’s Minutes, and also Southall’s firsthand account of living on Monroe Hill in the late 19th century; we feel that there is enough evidence to suggest that the law office was used as student housing for a period including the second half of the 19th century and into the beginning of the 20th century. At some point before 1917, the law office was rented out to faculty, and at least two of the range rooms previously occupied by students were also converted into a faculty residence.

Going into our fieldwork at Monroe Hill, we assumed that all of the rooms in the two range buildings were used as student dorms until converted into offices and the kitchen and bathroom for the faculty housing in the law office at some point in the twentieth century. However, upon completing our analysis of the material and archival evidence, we have concluded that there is a strong case to be made for several of the rooms being used for purposes other than student housing much earlier than was previously thought. We also believe it is quite possible that the law office was incorporated into the attached range and used as additional student housing, potentially even as early as the initial construction of the Monroe Hill ranges all the way up until the beginning of the twentieth century.