Method: Documentary Research

Documentary research is the use of texts, governmental and personal records, images, maps, and other documents to find more information about a subject. It often involves visiting archives and records rooms, but many collections have been digitized to allow remote access.

Our class visited the Albemarle County Courthouse and the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia, and also consulted the 1850 census and the Holsinger Studio Collection. We used these documents to try to better understand what the Birdwood property originally included, who lived there, how the property changed hands, and what elements of the site, such as the South Field and Formal Garden, once looked like (right: students doing documentary research at Courthouse, click to enlarge).

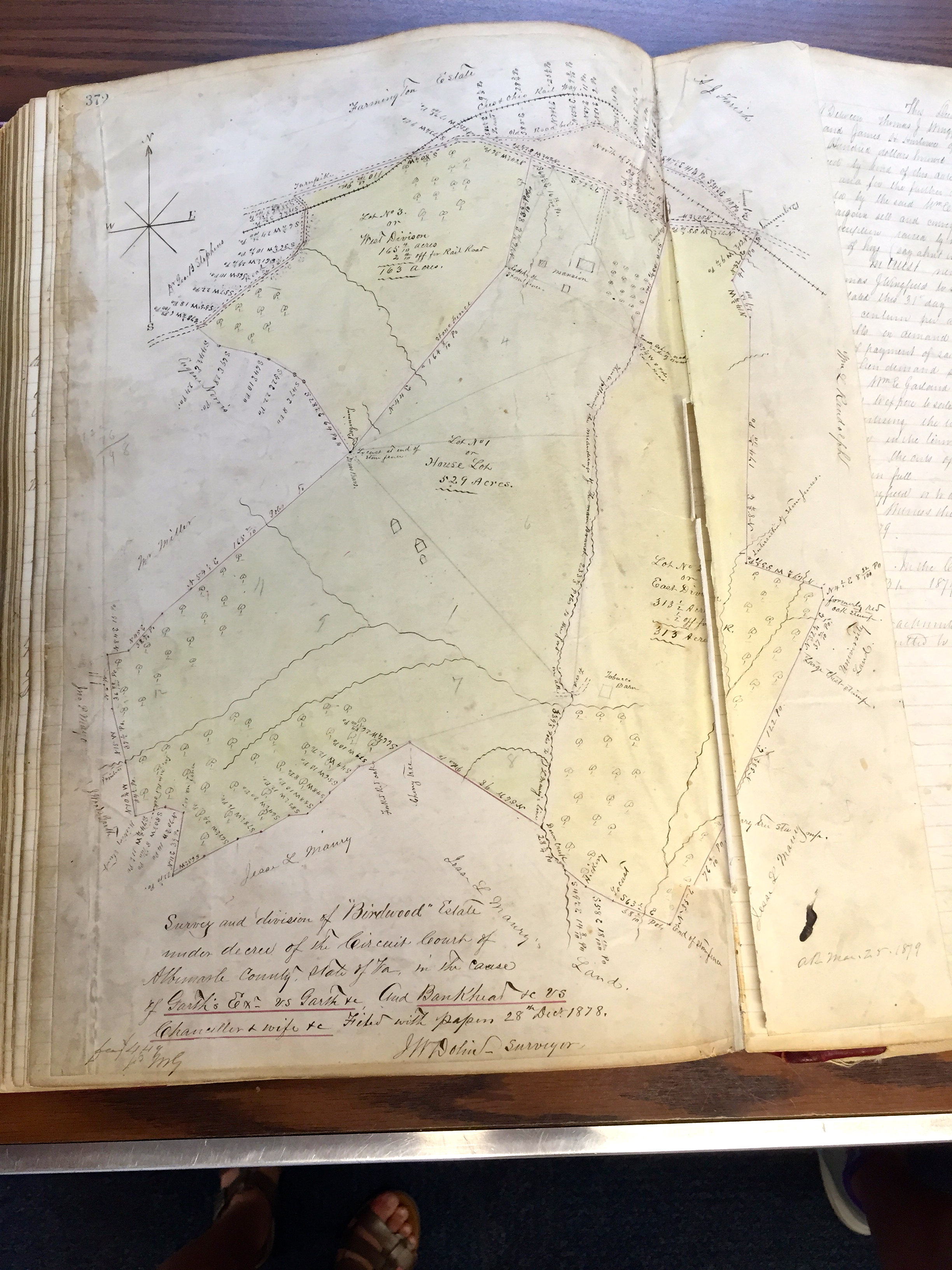

The Albemarle County Courthouse holds a wide variety of public records, such as wills, deeds, and marriage licenses, that can give researchers clues about the lives of past area individuals. Our class’s purpose for visiting this site was to use the documents to understand what the original Birdwood estate looked like and who lived there, both family and enslaved people. We were hoping to find the will of Birdwood’s first owner, William Garth, because we thought that it might have an accompanying document that listed an inventory of his possessions, including Birdwood and what other supporting buildings may have stood at the site. While we were unable to find an inventory, we did find an interesting plat map of the property and other information that allows us to better understand how the property changed hands after Garth’s death (right: Birdwood plat from Courthouse).

Census records can provide excellent information about the people who lived at different sites. These records list the names of the people who owned or lived at a property and also show data about age, gender, race, and literacy. The 1850 census is relevant for the Birdwood project because it was at this time that secondary sources claim Garth was living at Birdwood and had 52 slaves. The slave schedule record for the same year does show that there were some slaves at the property, but they did not add up to 52. It is possible that the 52 number indicated the total number of people enslaved by Garth, and our trip to the courthouse revealed that Garth had another estate called Midway, and 29 slaves were associated with that property, so the 52 could include these people as well.

The Holsinger Studio Collection contains a set of images of the main house, grounds, garden, and interiors at Birdwood. These pictures were taken by Rufus W. Holsinger (1866-1930) between 1917 and 1918 and are primarily valuable for this project for their views of the formal garden and backyard/south field. For the garden, the photographs show what was there before the Charles Gillette plan was drawn, which allows us to compare the plan with the photos and what we know today (left: Holsinger photo, view of garden, looking north). The garden’s layout and some other elements appear to share similarities with the plan, which encourages us to conclude that the full plan at least was never put in place at Birdwood. With the south field images, our class was trying to find out if there were more outbuildings in the south field, behind the house. A gallery of relevant Holsinger photographs can be found here.

The Holsinger Studio Collection contains a set of images of the main house, grounds, garden, and interiors at Birdwood. These pictures were taken by Rufus W. Holsinger (1866-1930) between 1917 and 1918 and are primarily valuable for this project for their views of the formal garden and backyard/south field. For the garden, the photographs show what was there before the Charles Gillette plan was drawn, which allows us to compare the plan with the photos and what we know today (left: Holsinger photo, view of garden, looking north). The garden’s layout and some other elements appear to share similarities with the plan, which encourages us to conclude that the full plan at least was never put in place at Birdwood. With the south field images, our class was trying to find out if there were more outbuildings in the south field, behind the house. A gallery of relevant Holsinger photographs can be found here.

While documentary research can provide fascinating and helpful information, it also has some limitations. One limitation is that documents are not always stored where one needs them to be. For example, in following the trail of William Garth’s will, we found out that after his wife died, instead of the estate being evenly divided amongst his children as he had requested, his descendants fought over their inheritances in a chancery court case that lasted 19 years. We thought that the property inventory we sought might lie in those records, but we learned that those documents are stored in the Library of Virginia in Richmond, and we were unable to visit this library to research. This is a frustrating reality of document-based research, but in many cases, looking at texts and images can help researchers find the answers to their questions.