Formal Garden

The Resource

In the University of Virginia’s Special Collections, there is a set of detailed plans by well-known Richmond landscape architect Charles Gillette (1886-1969) for the Formal Garden at Birdwood, drawn in 1928. At the time, Henry L. Fonda owned the property, and he sold it to J. D. Wilde in 1936. Although Fonda was the owner at the time of the plan’s drawing, but the name on the plan is “Miss M.G. McCleery,” which is strange as her identity and role at Birdwood are unknown.

An important question regarding the Formal Garden and Gillette plan is whether or not the plan was ever actually implemented. This plan divided the garden into four quadrants, each with the inside corner shaved off to create a small circle at the center (for a fountain or some other focal point). Each quadrant was to have held a different type of vegetation, such as one holding perennials, one a brick-laid rose garden, and the other two mainly trees and open space. The longitudinal axis of the garden was to be lined with more perennials, including peonies and chrysanthemums. The pool is described as “existing pool” and the plan proposes no changes to it (left: plan, Charles Gillette, 1928).

Our Inquiries

In order to answer the question of the plan’s implementation, several different tools were utilized. An important one was document-based research. The plan itself was a crucial document, as it told us what elements to look for and allowed comparison with the few garden elements that are extant today. In observing the landscape, in addition to the pool and overall rectangular shape, the only element of the plan that is visible today is a double row of peonies, spaced out in a way that is consistent with the plan.

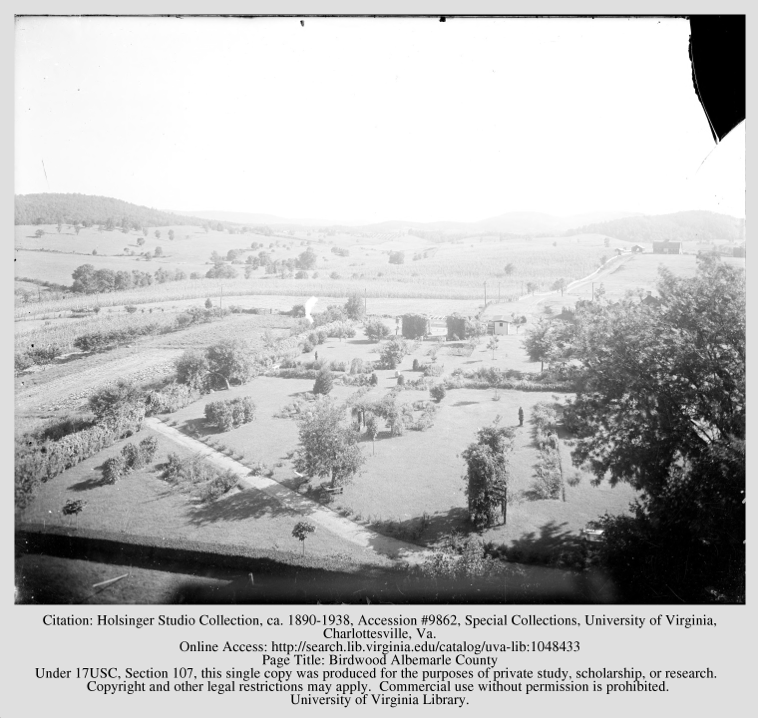

The Holsinger Studio Collection, found through the UVA library website, was another key source. These pictures were taken by Rufus W. Holsinger (1866-1930) in 1917 and 1918, about ten years before the plan was created, so they cannot be taken as evidence that any of it was implemented at the site. The images show a garden that was similar to what Gillette proposed, although significantly simpler. The four quadrants, basic shapes, and ornamental element placement are similar to what can be found in the plan, and the way that plants line the axis of the garden is also a feature of the proposal (right: view of garden layout, looking south, Holsinger, 1917). Our class carefully compared the plan, these photographs, Google Earth images taken over time, and our own observations of the current field to see if it is likely that the plans were followed.

The Holsinger Studio Collection, found through the UVA library website, was another key source. These pictures were taken by Rufus W. Holsinger (1866-1930) in 1917 and 1918, about ten years before the plan was created, so they cannot be taken as evidence that any of it was implemented at the site. The images show a garden that was similar to what Gillette proposed, although significantly simpler. The four quadrants, basic shapes, and ornamental element placement are similar to what can be found in the plan, and the way that plants line the axis of the garden is also a feature of the proposal (right: view of garden layout, looking south, Holsinger, 1917). Our class carefully compared the plan, these photographs, Google Earth images taken over time, and our own observations of the current field to see if it is likely that the plans were followed.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) is another tool that was used to investigate the garden and the possibility of the Gillette plan’s influence. Observations of the plan suggested that running the radar line over the entry axis and the southeast quadrant of the space would be the most helpful in deciding if the plan was used. This would allow the class to see if the remains of any lawn or ornamental features in the center or of a brick pattern from the proposed rose garden were hidden under the ground. Matthew Bartley, Geospatial Engineering Data Technician, and student intern Mohamed Ihsan operated the GPR machine and ran 5 transect lines over the garden area: the two that we had previously identified as being important, one at the north end, one over the longitudinal axis, and one over the former pool.

Data and Interpretation

Next Steps

In order to continue this project, we could do more documentary research and investigate the personal and financial records of the people who owned and lived at Birdwood at the time, as well as of Charles Gillette and his office. Mary Hughes, University Landscape Architect, whom we consulted for the project, suggested that oral histories would be a good way to establish a more concrete narrative for work like this. As for now, our conclusion that the plan was probably never realized allows us to advise that this space is most likely not significant as a work of the prominent landscape architect Charles Gillette.